This week Ludology met Narratology, and we looked that these two approaches to game studies. Again, there were diverse theories and approaches on how and/or if it was possible for a video game to have a narrative. Of course it’s possible, but the successful transmediation from a book/movie narrative to video game narrative is understanding that the player is experiencing and interacting with the narrative of the game in real-time, rather than observing the narration as in the former.

Honestly, this week there was so much to take in that’s its difficult to cover even a 10th of what I learned, read (and try to keep in mind), and experienced. The readings on narratives and story, characters, interactive digital stories, to worldbuilding and lore in 7 days, in addition to playing the games, finishing up assignment for this class, my other summer class, and work. I wish I had more time to do it right and let all the learning just soak in…

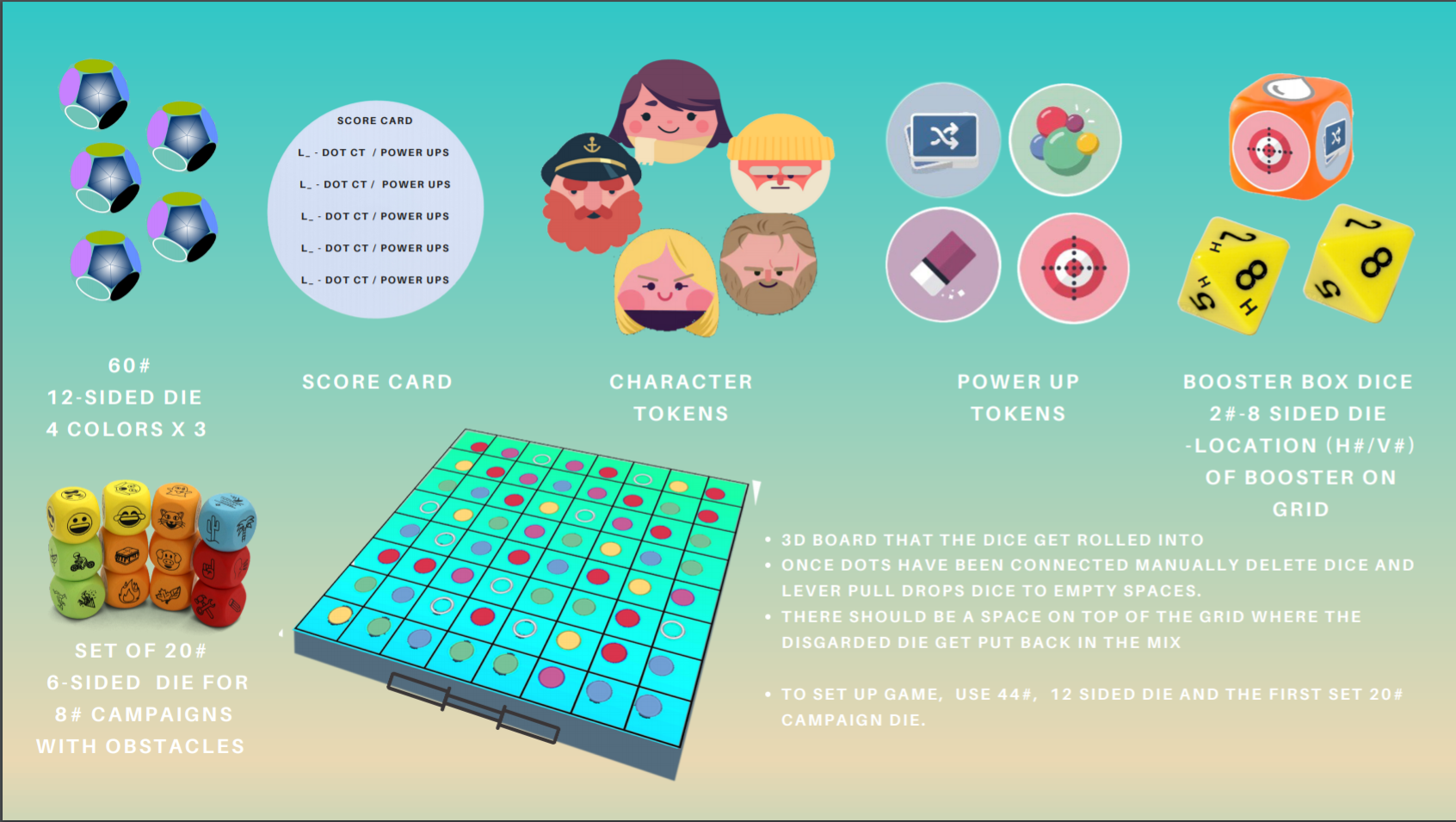

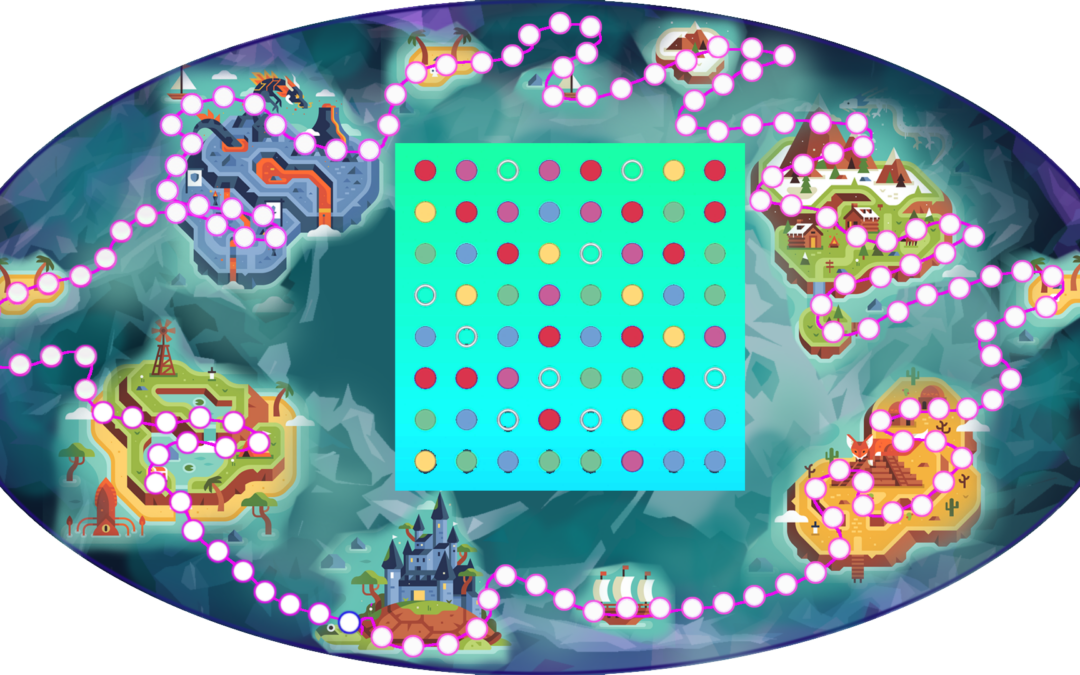

We were tasked with choosing a video game, dissecting the core components of the gameplay, then turning the video game into a board game. Which digresses a tiny bit from narratology, but had I applied it wisely….

Two Dots, a Board Game??

It was a great exercise in understanding the core mechanics of gameplay from week 2. Had I read Philip Pullman’s lecture “The Path Through the Wood” prior to my attempt at turning Two Dots into a board game, I think it would definitely have been more successful. I will admit it, the board game I attempted to create lacks rhythm and real purpose. Yet, had I applied Pullman’s “stay on the path” theory for creating a narrative to help form the soul of the board game, it could have worked.

Pullman, a writer/author, poetically helped me to understand how a narrative is created and that there are rules a story/the book follows. So, as the title goes the path is the book, with a beginning and an end; whereas, the endless fantastical woods are where the characters and the worlds within you book live.

Narrative and Gameplay

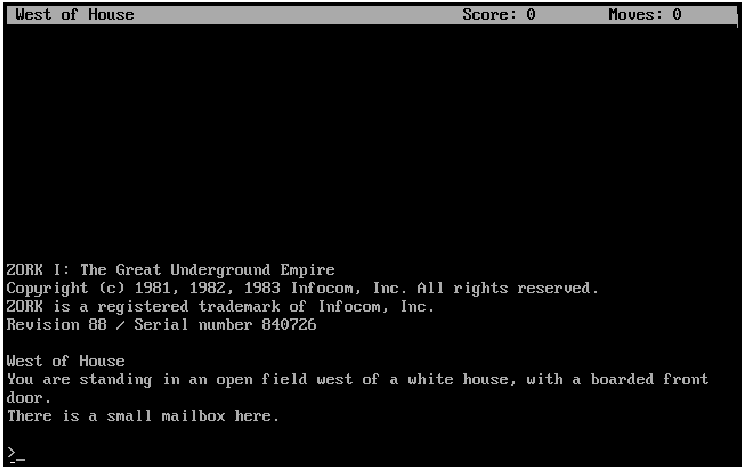

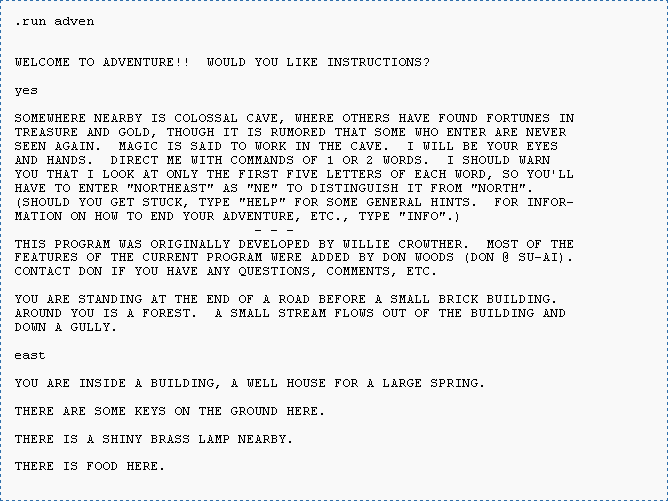

‘Hamlet on the Holodeck: The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace’ , Janet Murray’s 1997 ground-breaking forward-looking book on the rise of new genres of storytelling in the age of computing, provoked debates in the game studies field on the relationship between narrative and video games.

Jesper Juul in his July, 2001 article in Games Studies Journal ‘ Games Telling Stories?’ breaks down his theory of traditional storytelling narrative vs. the possibility of gameplay narrative. He starts with these three standard common arguments used for games being narratives:

- We use narratives for everything.

- Most games feature narrative introductions and back-stories.

- Games share some traits with narratives.

Then proposes three important reasons why games are non-narrative:

- Games are not part of the narrative media ecology formed by movies, novels, and theatre.

- Time in games works differently than in narratives… Story Time/Discourse Time

- The relation between the reader/viewer and the story world is different than the relation between the player and the game world.

In concluding, he states that ‘ you cannot have narration and interactivity at the same time; there is no such thing as a continuously interactive story.’ And urging the games studies community to not forget what makes games games…

‘rules, goals, player activity, the projection of the player’s actions into the game world, the way the game defines the possible actions of the player.’

Janet Murray in May 1, 2004’s essay . “From Game-Story to Cyberdrama”, Electronic Book Review, continues her exploration of forward thinking optimistic new game-story genres with new media practices. Her view is games are always stories (the word narrative is sparely used) and that ‘games’ and ‘stories’ have in common two important structures:

- The Contest, the meeting of opponents in pursuit of mutually exclusive aims. This is a structure of human experience…

contest between protagonist and antagonist. - The Puzzle, which can also be seen as a contest between the reader/player and the author/game-designer.

I tend to want to believe in her theories in approaching the ‘astonishingly plastic world of cyberspace.’

Worldbuilding and Lore

This is what draws players into a game’s magic circle, a reader into a book, an audience to a story.

I’m going to jump back a bit and mention the Games Study Journal’s article ‘Me and Lee: Identification and the Play of attraction in the Walking Dead’ (by Nicholas Taylor, Chris Kampe, Kristina Bell, volume 15 issue 1 July 2015 ISSN:1604-7982) which I found extremely helpful in seeing how Character, Identity, and Lore played out in their study. How these elements affected the way the player reacted and made decisions when faced with moral dilemmas.

In ‘The Game Narrative Toolbox ‘, Chapter 3: Worldbuilding, Tobias Heussner, 2015 explains in great detail the process of worldbuilding whether one approaches it from a macro – top down level or micro – specific outward level, the emphasis is on authenticity… even in a make believe fantastical world, it has to be believable.

The chapter highlights:

- How to use research (expressively stressed) and personal experience to inspire worldbuilding and make the world feel authentic.

- How to use World Archetypes as the foundation for world’s design.

- How to identify the worldbuilding details you need to share with the team versus what players need

to know. - How to give players knowledge of the world and ways to experience it through means other than

dialogue and story progression. - How to develop worlds for licensed intellectual property.

Most importantly, this reading informed me of how to begin or approach worldbuilding in a systematic manner. How do I start this daunting task?

And there is so much more to discuss that my mind is literally BLOWN. In order to complete my tasks for this week… I have to stop and get to work creating my game world. Til next week.

Recent Comments