I have been hesitant to upload the “beginnings” of my blog below that I have been working on since my return from 2 separate trips to Myanmar in 2015 and 2017.

The reason for my hesitation was the incidences of violence and “Rohingya” exodus from Upper Rakhine State into Bangladesh. I did not know how to address this, but knew it had to be addressed. At this moment I am still trying to understand the root of why this is happening.

Why has Aung San Su Kyi not commented on the situation? When and how did the term “Rohingya” evolve? Who are the “Rohingya”? What is the difference between Rakhine Muslins and Rohingya? How can this be resolved? And as one delves deeply into the this, I learn that the cause is not so simple, nor is the solution.

Last night, I had the opportunity to listen to a panel discussion sponsored by The Buddhist Action Coalition, Buddhist Council of New York and Union in the James Chapel at Union Theological Seminary: “The Rohingya Genocide”. And yet there still is no solution to the human suffering. I finally felt it was time… I was never going to get this right. As long as the predominant authorities ruling our planet Earth continue to battle, over power, resources, and wealth above human lives, these sad stories will continue to echo through time.

While I was growing up in the States, I remember happy events where my parents were surrounded by their good friends, whom they met back in Burma… from all denominations of religion— Christians (Catholic and Protestant), Hindi, Muslim, and Buddhist. They didn’t focus on their differences but came together to share their friendships, memories and celebrate their lives here in the States.

We hear of human injustices around the world constantly and most of us yearn for a solution. There must be a way that every person inhabiting this planet (our only home thus far…) can find a way to live harmoniously, share in peace and share in our mutual prosperity. Yet sadly, solutions seem to still escape us all… for now.

Without any answers, I find it impossible to comment objectively on this other than to urge each and everyone of us to let go of our prejudices and fears in the hopes of finding solutions to stop all injustices happening world-wide.

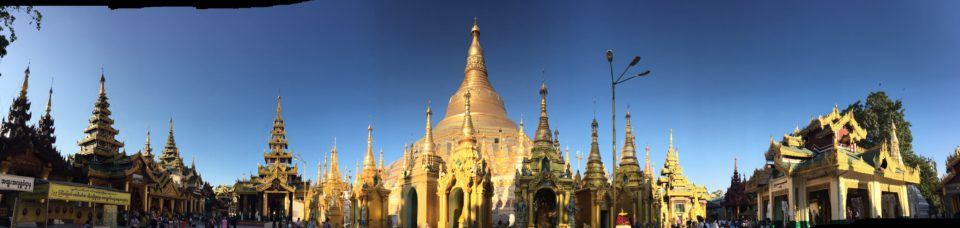

Shwedagon Pagoda, Yangon

Pieces of the Jigsaw Puzzle called “LIFE”

As a ‘first generation’ immigrant, arriving to the US at an age where memories had yet to be formed or understood, I often felt incomplete, missing some intrinsic part of me because I had little or no idea about the culture that had help form me.

In 2015, on hearing of Myanmar’s General Election a family trip was organized. It had been decades since I left Myanmar, but now the stars aligned and I was returning to the country of my birth.

After over 50 years of socialist military regimes, Myanmar had begun tangible steps towards democratization… Partial free elections!

The 2008 military-drafted constitution guaranteed that unelected military representatives take up 25% of the seats in the Hluttaw (parliament); have a veto over constitutional change; have control of national security (Ministry of Defense, Home Ministry Affairs, Border Security); and, the authority to assume power in a national state of emergency. This is what the generals called “disciplined democracy”. Well, if anything… a step in the right direction.

Htin Kyaw at Nobel – Myanmar Literary Festival in Yangon

The time between my first trip in December of 2015, before the National League for Democracy’s (NLD) Htin Kyaw took office and my return to Myanmar winter 2016. was literally 12 months. In that time, for as many things that had changed, understandably, so many more remained the same. Between the two trips, I spent a total of 48 days in Myanmar… close to a day, for every year that I had been away.

Formerly known as Burma (the name coined during British colonial rule after the majority ethnic group, the Bamar) until 1989 when the ruling military junta changed it to Myanmar. The two words actually mean the same thing; Bama is the spoken name of the country, while Myanma is the written literary name of the country.

The partial civilian government treads on a thin line as they try to introduce democratic reforms while not openly butting heads with military positions, to resolve internal ethnic conflicts, and give the people of Myanmar, the long awaited health, social, and economic improvements.

They are now negotiating to overhaul a country that has barely seen significant social or economic improvements since after WWII. After gaining its independence from the British on January 4, 1948 Myanmar then Burma, was beset by political infighting and conflict among the ethnic groups over political representation and autonomy.

Naypyidaw

This post is not meant to be political, or even critical. In this post, I hope to merely express my personal experiences and thoughts as I returned to the country of my birth for the first time through my westernized eyes. However, I felt that in order for me to understand how and why Myanmar is the country it is today, I had to do a bit of historical and societal research.

Initially, I thought this would be a simple research project. Compile the facts. Create a brief concise bullet point of historical events. Little did I realize, I was about to face a litany of diverging opinions and takes on Myanmar history. Which in the end, helped me to start to understand the psyche of the country.

If you just want to see the amazing panoramas, click here. (Sorry not functional link yet)… so here’s a few shots.

But for those die-hards read on. The brief, in a very distended nutshell…

Though there is evidence of nomadic Paleolithic cultures along the banks of the Ayeyarwady nearly 750,000 years ago and more recently, about 11,000 years ago in the Anyathian cultures, the Myanmar, we know today is a aggregation of ethnic groups and sub-groups that have migrated from India and China within last six millennia.

Myanmar with a population of about 55,000,000 has over 135 ethnic groups, sub-grouped into 8 groups which are officially recognized by the government. Each with their own history, culture and language. In addition, there are several groups which are not officially recognized ethnic groups (Burmese Chinese (2.5%), Burmese Indian (1.5%), Anglo-Burmese, Panthay, Rohingya , Burmese Gurkha, Burmese Pakistani and Tibetan)

For comparison, India with a population of over 1,350,000,000 has over 2000 ethnic groups and China with a population of over 1,370,000,000 has 56 ethnic groups.

The 8 major ethnic groups and sub groups:

Burman/Bama (est. 68%) comprised of 9 different ethnic groups;

Shan (est. 9%) comprised of 33 different ethnic groups;

Kayin/Karen (est. 7%) comprised of 11 different ethnic groups;

Rakhine/Arakan (est. 4% ) comprised of 7 different ethnic groups;

Mon/Taliang (est. 2.0% ) comprised of 1 ethnic group;

Chin (est. 2.0 % ) comprised of 53 different ethnic groups;

Kachin (est. 1.5% ) comprised of 12 different ethnic groups;

Kayah (est. .75% ) comprised of 9 different ethnic groups;

In sifting through books and internet articles, I found it difficult and frustrating to find correlating views about the early settlements in Myanmar, especially when it came to the timeline of first millennium settlements and cities. I’ve decided to make my conclusions by citing archeological, mitochondrial and linguistic sources, rather than chronicled and traditional histories. Though there is truth in the origins of chronicles, most all legends and myths are based on actual events and altered to suit the exigency of the authors and society they serve.

I am not a historian, anthropologist, linguist or archeologist. I just have a compulsive analytical personality and hope that in the end, present an unbiased brief.

The linguistic origins of the people of Myanmar can be divided into Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic, Tai-Kadai, Austronesian, and Indo-Aryan.

The Austro-Asiatic speaking Mon were the first of the modern ethnic groups to migrate to Myanmar around 800 BC from southwest China settling near the Thai border and southeastward. Several Mon settlements were established along the migration route into Thailand, and each created their individual cities and kingdoms. In Myanmar, the Mons evolved into a seafaring kingdom where Indian art, culture, Hinduism and Theravada Buddhism were integrated into their society through trade, at the port near present day Thaton. They revered art and literature. Archeological evidence dating from the 5th – 6th century AD shows their culture thrived in Lower Burma from Thaton to Pegu/Bago until they were conquered by the Pagan/Bagan expansion southward in the 11th century AD.

About 2nd century BC, the Tibeto-Burman speaking Pyu migrated from present-day Qinghai and Gansu province, by way of Yunnan, developing a civilization in the valleys of central Ayeyarwardy , Sittange River, and present day Taguang. The region where the Pyu city-states emerged in Myanmar were part of an overland trade route between India and China. For nearly a millennium, they flourished. And similarly as in the Mon Kingdom, through trade, introduced to Indian culture, Hinduism and Buddhism. The mid-9th century after, a hundred or so, years of persistent Nanzhao (of the Tai-Kadai speaking groups) raids originating again from the Yunnan province in China, marks the decline of the Pyu civilization.

The Pyu civilization fell to obscurity by the 12th century. Their culture and histories absorbed by the Mranma/Burman, a group of “swift horsemen” who migrated south arriving with the Nanzhao raids. Or they may have started migrating to the region before the Nanzhao raids, already living within the Pyu civilization. Either the case, archeological evidence shows that in the 9th century AD, they took over the territories occupied by the weakened Pyus to create the foundations of the Bagan Empire. Though little remains of the Pyu language and culture, their architectural, irrigation and city planning skills can be seen in the excavations of 5 walled Pyu city-states: Beikthano, Srikestra, Halin, Maingmaw, and Binnaka. The Burmans adopted the Pyu’s city-state plans (derived from Indian models) for their city and palace designs, and King Anawrahta of Bagan in the 11th century turned their irrigation systems into main rice granaries in Upper Burma. The Pyu language was finally deciphered in 1911 when the Myazedi Stone Inscription (circa 1113 AD Pagan Era) was translated. It is considered the Burmese “Rosetta Stone” written in four languages in Pyu, Old Mon, Old Burmese and Pali.

Bagan – Ananda Temple – Mandalay – Myanmar (Burma)

The Bagan empire under King Anawrahta (ruled 1044-1077 AD) is considered the first Burmese kingdom. Mahayana, Tantric and Theravada Buddhism, Hinduism and Animism existed in the pre-Bagan period, but after his southward campaign into the Mon State retrieving Mon Pali Canons in 1057, Anawrahta and sequential kings of Bagan embraced Theravada Buddhism infusing it with some indigenous Animist beliefs of the Nats. The fervor of meritorious temple building by Bagan rulers, ending in 1287 with the Mongol invasion by Kublai Khan, leaves us the extensive Bagan archeological site we see today. The architecture and Buddhist art found there shows a diversity of styles derived from Pyu, Indian and particularly Mon aesthetics to eventually form the Burmese style.

In the western coast of Myanmar a region bordered by the Bay of Bengal to the west, present day Bangladesh and Chin States to the north, and isolated from the Ayeyarwady Regions to the east by the Arakan Yoma, we find the Rakhine State. Archeologist have excavated two major Indo-Aryan cities, Dhanyawadi dating circa 3rd – 5th century AD and Vesali (6th-10th century AD) associated with east Bengal and southeast India. Similarly to the Pyu and Mon civilizations of that time, Hinduism and Buddhism coexisted and shared reverence. Muslim influences also emerged in the area through trade and commerce after the 9th century.

Though the region is named after the Tibeto-Burman speaking Rakhine , the ethnic group did not markedly settle in the area until the 9th century during the periods of Nanzhao raids in the upper Ayeyarwaddy region. And like most groups that migrate to a region with an established civilization, assimilated into the existing society. And yes… the history of this region, the dates and the origins of its inhabitants disputed by diverging texts and opinions. What is not disputed is that the many Rakhine kingdoms maintained their independence from the Burmese until the conquest of the Mrauk-U dynasty (1429 – 1785 AD) by the last Burmese kingdom, the Kongbaung dynasty in 1785. The Mrauk-U kingdom was under Bengali suzerainty from its nascency in 1429, when Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah helped exiled Rakhine King, Meng Soamun Narmeikhla, regain his kingdom from the first Burmese Ava Kingdom, to 1531. In the beginning of the 1600’s, Mrauk U (Mrohaung), developed into an important trading hub welcoming Portuguese traders and the Dutch East India Company.

Another ethnic group to have significant influences in Myanmar history are the Shans, a Tai-Kadai speaking group with origins from southwest China. Their southward migration into Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam and even into India came in waves circa the 7th – 14th century AD. There is evidence that the Shans were one of several groups entering Myanmar with the Nanzhao raids. During the Bagan Empire the Shans in the east through marriage created an alliance with the Bagan maintaining their autonomy. After the fall of the Bagan and the Mongol invasion of the Yunnan province, a large influx of Tai-kadai settlers from Yunnan migrated south strengthening their existing settlements in Southeast Asia.

The post-Bagan period of Myanmar history is delineated by several kingdoms assuming power over different regions and attempting the unification of the country. Beyond this point bloodlines have merged through inter-marriage and few rulers are of a pure ethnic group. The Mons of Hanthawaddy Kingdom in the south from 1287-1582; the Ava Kingdom of Burmese in the northern Ayeyarwaddy region from 1364-1527; in the west the Mrauk-U Kingdom of Rakhines (1429 – 1785 AD); the Shans States of Mong Yang and Mong Kawng (circa 1300 – 1557) to the east; the central Burmese Toungoo Dynasty in 1486 to 1752 considered the second unification of Myanmar; and finally, the Kongbaung Dynasty from 1752 to until 1885. The third and final Anglo-Burmese war ended the Myanmar monarchy when the British captured and exiled the last king of the Kongbaung dynasty, and annexed all of Myanmar as a province of British India.

I realize I just clumped Myanmar’s 600 years of history into the previous paragraph of less than 100 words not mentioning other relevant minority groups that migrated to Myanmar before the British colonial period: the Karens, the Chins, the Kachins, the Kayahs and their subgroups. However, I hope to be able to fill in the details as I start the heart of my blog… my journey back to Myanmar after decades away.

Please excuse the lack of citations for the information above.

Below is a list of sites, books and journals I used to compile data:

http://www.burmalibrary.org/show.php?cat=-1&sl=0

http://www.newmandala.org/myanmar-bibliographies-booklists/

https://www.worldtravelguide.net/guides/asia/myanmar/

https://www.britannica.com/place/Myanmar

http://www.altsean.org/ChronologyHome.php

http://www.cfob.org/burmaissue/ethnicGroups/ethnicGroups.shtml

http://www.oxfordburmaalliance.org/ethnic-groups.html

https://www.burmalink.org/about-us/who-we-are/

http://factsanddetails.com/southeast-asia/Myanmar/sub5_5a/entry-2996.html

https://forwhattheywereweare.wordpress.com/category/myanmar/

http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/myanmar-population/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myanmar

http://journalofburmesescholarship.org/

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-12992883

http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/burma.htm

https://newint.org/features/2008/04/18/history/

https://myanmars.net/index.php

http://althistory.wikia.com/wiki/Myanmar_(Burma_Ascension)

http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/myanmar.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rohingya_conflict

http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume14/Article1.htm

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41046729

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-41020738

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rohingya_people

https://bmcevolbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2148-14-17

https://www.nature.com/articles/srep09473

https://macauhub.com.mo/feature/new-book-reveals-hidden-history-of-portuguese-of-burma/

Burma – Art and Archeology -Green and Blurton

The Vanishing Tribes of Burma – Diran

Buddhist Art of Myanmar – Fraser-Lu and Stadtner

Back to Mandalay – Burmese Life, Past and Present – Lewis

History of Myanmar since Ancient Times – Traditions and Transformations – Aung-Thwin

History of Modern Burma – Charney

Burma/Myanmar – What everyone needs to know – Steinberg

Greeting from Myanmar – Bockino

Blood, Dreams and Gold – The Changing face of Burma – Cockett

Where China Meets India – Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia – Myint-U

Experience Myanmar (Burma) 2016 – Rutledge

Women in Modern Burma – Rutledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia – Than

The Journal of Burma Studies – Volume 10 2005/06 –

Myanmar Policy Briefing -18 – January 2016

The Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship – Vol.1 No.1 Aug 2016 – Thawnghmung

History of Myanmar – The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations – Topich and Leitich

Recent Comments